Episode 326 - Legal Genealogist Judy Russell Talks About the Law Behind Quarantines and a New Year of Public Domain Releases

May 03, 2020

Host Scott Fisher opens the show with David Allen Lambert, Chief Genealogist of the New England Historic Genealogical Society and AmericanAncestors.org. David begins by talking about his recent experience of visiting Lexington Green and Concord Bridge on the 245th anniversary of the beginning of the Revolutionary War, while wearing a mask for another historic event. David also made a fascinating family photo find on Facebook featuring David as a child! He’ll explain. Then the guys talk about two half sisters who only recently found each other. Now they’re stuck together on a lonnnng visit, in quarantine! A French soldier, killed in World War I, was memorialized by his parents who sealed off his bedroom with brick. That brick has now come down and its remarkable what is in that room! The guys will go through some of the items. Then, Fisher and David talk about a recent study that has determined the likely cause of death for the crew members of the Civil War submarine, the Hunley.

Next, Fisher begins his two part visit with the Legal Genealogist, Judy Russell. First, Judy shares the history of legal quarantine. It goes back much further than you might suspect! In the second half, Fisher and Judy discuss the exciting prospects for 2020 concerning material from 1924 that has come out of copyright and into the public domain.

Next, David returns for another couple of great listener questions on Ask Us Anything.

That’s all this week on Extreme Genes, America’s Family History Show!

Transcript of Episode 326

Host: Scott Fisher with guest David Allen Lambert

Segment 1 Episode 326

Fisher:And welcome to another edition of Extreme Genes, America’s Family History Show and ExtremeGenes.com. I am Fisher, your Radio Roots Sleuth on the program where we shake your family tree and watch the nuts fall out. Great to have you along, genies. And I’m doing the whole show in social isolation direct from Fisher Castle, and hope you’re doing okay and everybody is staying safe. We’re going to talk about quarantine today, you know, the legal side of this whole thing. We’ve got the Legal Genealogist, Judy Russell coming on later on for a couple of segments talking about that. Also, all the new images that are coming out, all the things that are in the public domain as a result of the change in the law recently. Smithsonian recently released 2.8 million images you can find online. We’re going to talk about that as well, so that’s going to be a lot of fun. If you haven’t signed up for our “Weekly Genie Newsletter” yet, now’s the time to do it. Just go to our website, ExtremeGenes.comor to our Facebookpageand you’ll find a way to get there. We would love to have you as part of that. Right now, it is time to head out to Boston or somewhere in that neighborhood to the home of David Allen Lambert, the Chief Genealogist of the New England Historic Genealogical Society and AmericanAncestors.org. David, you are doing so well. You’ve had a big week!

David: I have. In fact, I had tweeted on April 19th when it was 245thof Lexington and Concord and then my wife said to me, “We need a road trip.” So, we put on our masks and got in our van and we headed to Lexington and Concord on the 245th anniversary of the battles. First went to Lexington Green, got out, took pictures. I was photobombed by my family a number of times.

Fisher: [Laughs]

David:I got to take pictures, which is great fun, so now we have the historical place with the historical time period now wearing masks.

Fisher: Yeah.

David:[Laughs]

Fisher:You’ve got to imagine there are not a lot of people who have had their photos taken with masks on.

David: Yes, there were a few, I mean, not so much in Lexington Green, but when we got to Concord Bridge, it was definitely social distancing. You’ve got a lot of people on bikes, which make these narrow, old New England roads, the battle road, if you will, a little treacherous when you have bikes on both sides of the road and two lanes of traffic.

Fisher:Sure. Yeah, amazing.

David:We got to Concord Bridge, crossed over there, and it was just really special to share with my daughter the fact that our own ancestor had marched on the alarm, not made it to Lexington and Concord obviously, but actually made it to the battle road and back when they surrounded Boston.

Fisher:Wow!

David: So, that night I went home and I was feeling a little historic. Well, not that I don’t at this age anyways, but I decided to look at the local historical society page on Facebook for my town historical society and I looked and I see a photo. I said, “Oh, that’s the parade in 1976 from our town’s 250th and also the bicentennial.” And I looked and I said, Who’s the kid in the purple pants? Oh, it’s me.”

Fisher:[Laughs]

David:And directly behind me was my grandmother. A picture I had never seen. I remember she was sitting in a folding chair watching the parade, and right in front of me to my right as I get my hands folded is my cousin, Dina who was bored out of her socks!

Fisher:And you remember all that?

David:I do. I do. I was just about seven years old when this happened and I always thought it would be fun to see if I’m in a crowd picture somewhere, but now I know where I was in a crowd. I thought I was actually a little further down the street.

Fisher:[Laughs]

David:But yeah, I’m going to have to scour other ones and see if there’s a video and that sort of thing, so it was a lot of fun to find myself.

Fisher:Yes.

David:But, purple pants, I look like little Bobby Brady.

Fisher: [Laughs] 1976, that’s incredible.

David: [Laughs]

Fisher:All right David, let’s talk about this though. Here’s a sister who discovered a couple of years ago that she had a half-sister. So, we’ve got these two half-sisters, one in New Zealand and one in England. They only met last year for the first time when the New Zealand sister flew out to England and they got together and they hit it off and they were so excited and they had never met. I guess one was aware of the existence of the other and they went through the process and figured it out and then they made contact. Well, bottom line is now, the half-sister from England goes over to visit half-sister in New Zealand, and now she’s stuck living with her in quarantine right now during the pandemic.

David: It’s a great story on Extreme Genes. I especially liked the one where they are holding two knives at each other.

Fisher: Yeah. [Laughs]

David:I thought to myself, “Hmm, things are getting a little testy at the old family home.” I would think that this will give them a bonding experience they never thought they would have.

Fisher:Totally.

David: I’m glad they’re getting a time to catch up. I mean, one’s 71, the oldest, Margaret and the younger one I believe, is just a few years younger, she’s in her mid 60s. So, I’m really happy for Margaret and Sue that they found each other. I have a similar experience as I remember from a couple of years ago when I found an adopted sister of mine, my sister Donna. In fact, Donna, I just want to report, is now over COVID.

Fisher:Oh wow! Wow!

David:Yeah, she works as a nurse, and had contracted COVID somewhere, probably at the hospital.

Fisher: Sure.

David:And she is now cleared and is back to work.

Fisher:My goodness.

David:But she had the follow up tests and you just never know who you’re going to find in your life. And for me, finding Donna is probably as exciting as it was for Sue and Margaret, but I can tell you Donna’s not living with me.

Fisher:[Laughs]

David:[Laughs]

Fisher:That’s true.

David:You know Fish, that story you shared with me earlier today about the French soldier that they found his room bricked up for nearly a century.

Fisher:Um hmm.

David:Well, the Americans are probably going to read the name on the story as Second Lieutenant Hubert Guy Pierre Alfonse Rochereau, but I’m sure your French accent will sound better.

Fisher:[Laughs] No, no, no let me help you. It is Second Lieutenant Hubert Guy Pierre Alfonse Rochereau. How’s that?

David:Ah.

Fisher: Yeah.

David: Very good. Yes, he died in an English field hospital ambulance on the 26th April 1918, almost 102 years ago. But his parents created his room like a shrine, and the pictures were amazing. If you have a look at ExtremeGenes.com for our news stories, you’ve got to look at this one.

Fisher:This one is incredible, because they bricked up the room and they had an arrangement with the people who took the house over after they left that it would stay bricked up for 500 years. It’s absolutely incredible! It’s got uniforms, books, his bed, all kinds of documents, boots freshly shined sitting under his desk. I mean, it’s just absolutely unbelievable.

David: That’s about all I have for interesting stories from Stoneham, Massachusetts. But I do want to let you know if you’re not a member of American Ancestors, you can save $20 if you use the code “AprilResearch20” this month.

Fisher:All right David, thank you so much and we’ll talk to you a little bit later on as we come back for Ask Us Anything. But coming up next, we’re going to chat with the Legal Genealogist, Judy Russell about quarantine, the laws surrounding it and lots of other stuff, when we return in three minutes on Extreme Genes, America’s Family History Show.

Segment 2 Episode 326

Host: Scott Fisher with guest Judy Russell

Fisher: All right, we are back for another segment of Extreme Genes, America’s Family History Show and ExtremeGenes.com. Always a pleasure to have my good friend Judy Russell, the Legal Genealogist come join us today. And boy, Judy, there’s a lot of legal talk going on right now. I thought it would be fun to have a look into what we got going with quarantines, the legal side of that. The historical side of that because we’re sure seeing it today. We’re living through history.

Judy: We’re absolutely are. And you know, our own history is part of this. It’s just one little tiny piece. Because we have to look back a long way to get to the start of human history and disease. Let’s face it it’s been around as long as we have.

Fisher: It’s true. It was a long time before anybody back then even figured out what caused disease to spread. But obviously, you can go back to Shakespeare’s time. You can go back to ancient times.

Judy: Absolutely. You know, the first one that people really started thinking about in terms of keeping people apart at a time when disease was coming through was leprosy.

Fisher: Yeah.

Judy: Now, we’re talking literally Biblical times.

Fisher: Right.

Judy: The separation there, you don’t have a real legal framework for it until, okay, we’re still talking ancient history here, but the first kind of law that setup a quarantine was really 549 and it was the Emperor Justinian, the Byzantine emperor because what they were having was Bubonic plague. So, anybody coming in from a plague area had to be separated, isolated, for a period of time to try to get the influx under control.

Fisher: It was like they were able to actually observe the fact that if you could separate people with disease, other people wouldn’t get sick. But they probably had no idea why.

Judy: No idea why, whether it was airborne, or waterborne. I mean, let’s face it. We separated out the cholera people with the notion that it was airborne and it turned out to be a waterborne disease.

Fisher: Yeah.

Judy: So, we don’t always know what we’re doing, historically.

Fisher: [Laughs] No.

Judy: But who knows if we know what we’re doing today?

Fisher: Well, I think that’s true. And I think we’re seeing the effects of that where there’s so much information we just don’t know, right, till the testing. At least we know what we don’t know to some extent in terms of what we got to find out.

Judy: We’ve got a better idea today, thank heavens, with modern medicine.

Fisher: Yeah. Sure.

Judy: But a notion of keeping people apart and trying to keep disease from entering the community, has really been around for a very, very long time. Now, the word “quarantine” didn’t really start getting used until near the time roughly of the Black Death, the big plagues of the 14th and 15th century.

Fisher: Sure.

Judy: Venice of course was a city state at that point, it was the very first formal quarantine system. And they required ships to sit outside, at anchor, out of the harbor for 40 days. And that’s why it’s called quarantine. Quarantine is Latin. You know, it comes from the Latin for 40.

Fisher: Then you’re saying though that the law came into effect in Europe at that time?

Judy: Essentially, yeah. I mean the notion that they suspected that it was coming in via ships, via the sailors, and that by keeping the ships from coming in while it could still be contagious, that it would help. So, they started with the institutional quarantines back in the 1300s. You’ve got the Duke of Milan keeping people out.[Laughs]

Fisher: [Laughs]

Judy:He literally made people suffering from plague go outside the city until they either recovered or died.

Fisher: Wow. And who would be there to take care of them, right? Nobody.

Judy: Oh, yeah. Fortunately, back in that time period it was predominantly the church and the nuns.

Fisher: How about in North American history, going back colonially, do we have any laws that you’re aware of with quarantine periods?

Judy: Oh yeah, almost right from the very beginning. You look at Massachusetts for example.In 1647 there was the first ordinates setup by the City of Boston saying that arriving ships had to stop at the harbor entrance to be inspected for medical conditions.

Fisher: [Laughs]

Judy: There was a Smallpox epidemic in New York City in 1663. Now, that point we’re just changing over what, from the Dutch to the British.

Fisher: From the Dutch to the English, yep.

Judy: And they said the same thing. Anybody coming from an infected area couldn’t enter the city until the sanitary officials said they could, so right from the very start. As a matter of fact, probably by the early 1700s.Essentially, every major town and city on the Eastern seaboard had a quarantine law.

Fisher: Isn’t that interesting? And you know, if you go back to the period in the 16 teens just before the Mayflower got there, of course there were the European fishermen who came along and they wound up infecting the Indian population there. The Native American population was decimated. Towns that were completely gone. And the Natives knew that it was exposure to other people. Yet, I’m sure they had no idea exactly why it worked that way.

Judy: No idea, and no protection. And this continued of course. The Native American population being devastated by Cholera and by Malaria, and by all the diseases that by that time some of the English based colonists had gotten some community towards, or at least some exposure to.

Fisher: Yeah, absolutely.

Judy: We’re talking all kinds of diseases. You remember when you were a kid and you had measles.

Fisher: Mumps.

Judy: And German measles, and Mumps, and all those things and they quarantined us.

Fisher: Yes they did.

Judy: You couldn’t leave your house.

Fisher: Except for people who wanted to expose their kids to something so they’d get it out of the way so they wouldn’t have to deal with it later, you know?

Judy: I’m one of seven full siblings, eight with a half sibling, and my mother’s attitude was, “If one get’s it, put them all together.” Because eventually they’re all going to get it and at least we’ll get it over with.

Fisher: Right. It’s just kind of a rite of passage.

Judy: Yep, you did have some of that. But the more serious diseases, we’ve always had a more serious reaction to it. And the thing that’s kind of cool for us as genealogists is when you find that either directly recorded because there’s an actual record of quarantine or you find residual evidence of the implications of it in your own family history.

Fisher: Sure. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Judy: My grandmother, for example, was born in Texas and at a very early age taken to what was then Oklahoma territory and later became the state of Oklahoma. And her father, my great-grandfather, was a successful bidder in the big pastor opening there in Oklahoma. The homestead law started so he had to setup the homestead and did improvements, and you couldn’t leave the homestead without a good excuse. Well, the documents where he proved up that homestead said they had only been off the homestead for one period of about six months and the reason was quarantine for Smallpox.

Fisher: Oh wow. Wow!

Judy: And there you have that evidence in the land documents of the impact of a medical emergency and quarantine. And that’s not even a story that got passed down through the family. That’s just literally tripping across it in the records of the day.

Fisher: Right. You can’t really look for it either, right? I mean, nobody is going to be expecting it unless you had people in a certain area in a certain time and you might be curious about that. I had an ancestor who lived in Sweden in the 1700s. I want to say 1710, it might have been a little later than that, and they had a terrible plague go through there at the time, and this one ancestor was the only surviving child in her family. Everybody else, including her parents, were wiped out. And I’ll just look at that and it’s like man, that one person who survived there. Because you know it’s such a domino effect Judy. If you take one ancestor out hundreds of years ago, everything is different for thousands of people, you know?

Judy: No question. And this doesn’t require us to go all the way back to that but what it does make us do as genealogists is when we see things like a set of deaths over a relatively short period, we need to start looking at why, and what was going on at that time in that place. My grandmother’s cousin in Lamar County, Texas had a whole bunch of kids in the 1920s and 1930s. And when the Texas death certificates were digitized and put on to Family Search, up popped a whole series of death certificates in like a two year period there in Lamar County just in this one family.

Fisher: Ha!

Judy: And that sent me looking to the mortality records and there was a Whooping Cough epidemic in that community at that time. And it literally tookthe last five children in that family were a set of triplets and a set of twins. Four of them died.

Fisher: Ugh. You know, I’ve seen the family on my wife’s family bible where they lost both parents two weeks apart and two children as well. I’ve never been able to find out what it was. But you know what it was, it’s just which one.

Judy: You know there was an illness going through.

Fisher: Yeah. Absolutely. And that’s the curious thing. But it just struck me as you said that 1870 is when this thing happened and I don’t know if it’s before or after the census. I’m going to have to double check because, yeah, mortality indexes also and the records that come up in the census at that time could be very helpful.

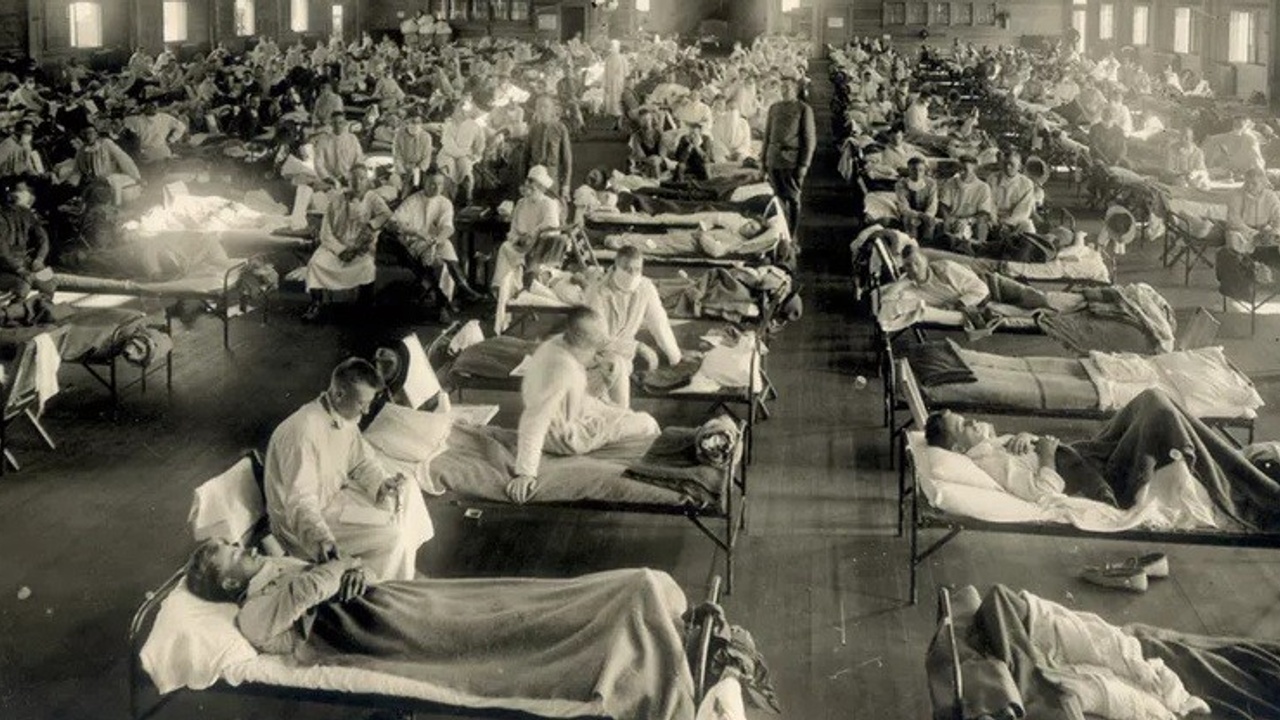

Judy: The census, newspaper articles at the time, they tended to be much more detailed about deaths than we report today, but it explains so much from a genealogical perspective. It is true, you know, my mom’s family is from Texas and lots of vital statistics didn’t get recorded really early in Texas. It was a very late adopter for a lot of vital recordation. But you go to 1918, 1919, 1920 there are huge gaps in death recordation in particular. Well, yeah.

Fisher: [Laughs]

Judy: Because there were so many people dying of what we call The Spanish Flu. They weren’t keeping up.

Fisher: She’s Judy Russell. She’s the Legal Genealogist. And Judy, we’re going to take a break.We’re going to come back. We don’t want to talk about disease anymore, [Laughs] because it’s just so overwhelming at this point. But that was all great stuff. But we’ve got to talk about copyright, right, because so many things are changing now with the change in the law and so many cool items coming available to all of us. We’re going to talk about that when we return in five minutes on Extreme Genes, America’s Family History Show.

Segment 3 Episode 326

Host: Scott Fisher with guest Judy Russell

Fisher:All right, back at it on Extreme Genes, America’s Family History Show and ExtremeGenes.com. Fisher here, your Radio Roots Sleuth, with my good friend Judy Russell, the Legal Genealogist, and we’ve been talking about quarantine today. Let’s talk about happier things, Judy, and that is stuff coming out of copyright into public domain. I know this is one of your favorite topics because I’ve heard you speak on this many times. But this is good stuff, especially with the news coming out of the Smithsonian.

Judy: It is. And the reality is that the more things that come into the public domain, of course, it means by definition, that we can use them. We can change them. We can modify them. We can play with them. All without being concerned about violating anybody’s copyright and getting ourselves into trouble. So, having things move out of the status of copyright into the status of public domain is a real game changer for researchers, for historians, for bloggers, and for people who just want to send things off on the internet.

Fisher: Sure. Well, you think about it, obviously public domain has been around forever and maybe somebody who is listening is going, “What are you talking about?” Well, public domain movement from copyright was kind of on hold for a long time here.

Judy: It sure was.

Fisher: So Judy, fill them in on that.

Judy: That’s the big change and that just occurred January of last year, for the very first time in 20 years. What should have been happening, is that every year on January 1, we should have gotten a whole year’s worth of materials. So, whatever was published in the 1900 should have come into the public domain. Whatever was published in 1901 would come into the public domain the next year. But, back in the 1970s when a couple of commercial companies got nervous about losing some of their copyrights, they got a 20 year extension. So, from 1998 to 2018, not a single solitary item moved out of copyright status into the public domain. And I’m telling you, on December 31st 2018, we were all sitting there holding our breaths, watching that clock tick over, and son of a gun, it happened. There were no changes in the law. Everything published in the year 1923, which was the first year that hadn’t been opened, came into the public domain.

Fisher: Right.

Judy: January 1, 2020, everything published in 1924, and as long as nobody gets their knickers in a twist in congress and does anything to change it, then January 1, 2021, we’ll get all of 1925.

Fisher: That whole law really had to revolve around Mickey Mouse.

Judy: I’m sure anybody who had a commercial interest in a copyright, I think at this point even the Disney Company is kind of a little bit easier with the notion of Steamboat Willie falling into the public domain.

Fisher: Sure.

Judy: And I don’t know that there’s any political will by anybody to stop the clock again.

Fisher: I was just concerned because that was 1928, right? That’s just a few years down the line. It’s like, okay when we get to 2024 are we going to have somebody say, wait a minute, we can’t let Steamboat Willie out, you know?

Judy: It could happen.

Fisher: Yeah.

Judy: And that means that we as researchers and historians who want to use this material are going to have to be very diligent in keeping an eye on any movement in congress to shut this down again.

Fisher: Sure.

Judy: Because what happens if we’re allowed to move things into the public domain, is that it opens up the opportunity for things like this fabulous set that’s just been released by the Smithsonian Institution.

Fisher: Oh, yeah. Let’s talk about that a little bit. I mean, there’s 2.8 million pieces just recently.

Judy: Yeah, 2 and 3 dimensional images across all of its collections and what they did was they put it onto an open access platform. So, we can look at it. We can download it. We can play with it, and use it anyway we want, illustrate our family histories and our blogs, and our presentations. It’s a wonderful gift from the Smithsonian to everybody, to be able to use this.

Fisher: Absolutely, and they’re talking about 200,000 more images just this year.

Judy: Just this year. You look at the Smithsonian and of course, the Smithsonian is not a single building, its multiple portions. The National Museum of the Native American and the National Air and Space Museum, all of those are Smithsonian Institutions. They hold somewhere in the neighbourhood of a 155 million items.

Fisher: Ooh.

Judy: That could all be digitized and made available to us, artefacts and data-sets, specimens, and models of all kinds of neat things. It’s a wonderful opportunity and the Smithsonian took the lead and made it all available under a creative common zero licence, which means we can use it for anything that we want.

Fisher: Isn’t that something? How long do you think it will take them to digitize a 150 million pieces like that?

Judy: Ah, let’s see, at 200,000 a year, you do the math.

Fisher: [Laughs]

Judy: I’m probably not going to live long enough to see all of it get online.

Fisher: No, if they stick to that pace you’re right. They’ve got to do a lot more than that. Heck, if they did a million a year it would take 150 years.

Judy: It would take a very long time.

Fisher: Yeah.

Judy: So hopefully, they’re picking the best and the least esoteric items to digitization.

Fisher: Right, right.

Judy: But yeah, the movement to make repository collections available open source and so many institutions have done it. The New York Public Library, the New York Municipal Archives, the National Archives, the Smithsonian, so many places are taking a look at their collections and determining what realistically can be made available in a digital format . It’s such a game changer for all of us.

Fisher: So, let’s look at this year now. 1924 is out. What is in the public domain now that wasn’t last year that might be of greatest interest to genealogists?

Judy: You know, I took a look at what HathiTrust is doing. Now, HathiTrust of course is HathiTrust Digital Library and they’re a collection of libraries, academic, other repositories that does a lot of digitization. And they’ve done a collection of all of the things that were published in 1924 and so came available as of January 1, 2020, just English language books about genealogy published just in the United States and there’s something like a thousand titles.

Fisher: Wow!

Judy: Fifty thousand books overall, so, history, science, law, math, personal histories, and all kinds of things, but using the keyword genealogy, more than a thousand items.

Fisher: Wow! That is huge.

Judy: Things that were published in 1923 that came available a year ago, just genealogy books, 1,200 items.

Fisher: Wow! And you think about the pictures and the music that comes out that you can use to illustrate a story, whether you’re doing it online or you’re doing it on paper, obviously couldn’t use audio there, but I mean there’s just so much that comes out, it makes you blow your mind when you think about writing a history or creating a site or something.

Judy: When we started, when copyright began in the United States back in the early days of the Constitution, you could only get a copyright for like 20 years.

Fisher: Right.

Judy: And here we’ve got things today, the copyright law says that anything that you write or that I write, even out of state, is going to hold the copyright for 70 years after our death. So, copyrights last a very, very long time here in the United States. So, getting anything officially, formally out of copyright is a real net plus to all of us.

Fisher: She’s the amazing Judy Russell, the Legal Genealogist. Go to TheLegalGenealogist.com and you can follow her blogs there. Always great to talk to you my friend. Thanks for the insight. You’ve got me excited now, I’m really going to go over and see what the Smithsonian has already posted there.

Judy: Thanks for having me on.

Fisher: And coming up next, David Allen Lambert joins me again for another round of Ask Us Anything on Extreme Genes, America’s Family History Show in three minutes.

Segment 4 Episode 326

Host: Scott Fisher with guest David Allen Lambert

Fisher: All right, we're back for Ask Us Anything on Extreme Genes, America's Family History Show and ExtremeGenes.com. Glad to have you along. It’s Fisher here, your Radio Roots Sleuth with David Allen Lambert back from the New England Historic Genealogical Society and AmericanAncestors.org. And David, we have a question, because as you just mentioned earlier in the show, we have the 245th anniversary this past week of Lexington and Concord and kind of in connection with that, we have a question from Missy in San Pedro, California. She said, "I had an ancestor who was in the crowd when the Boston Massacre occurred. Does that make me eligible for the Daughters of the American Revolution?" That's a good question. And since you're an officer in the SAR, the Sons, David, you probably have an answer for that.

David: I do. And unfortunately Missy, that doesn't qualify them. First off, you have really no way of proving that they were there, unless of course they were a victim. That being said, the Daughters of the American Revolution and the Sons of the American Revolution do not qualify the Boston Massacre spectators.

Fisher: Um hmm.

David: You don't know, in the future, maybe one of the victim's descendants could quite possibly be put in for patriotic service.

Fisher: Sure.

David: The patriotic service is a little different. You ancestor may have later on fought in the war, so that early service doesn't matter anyway. So, you could go through and you can see if he's on a muster roll, there's plenty of copies of books, for instance the Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors in the Revolution is on Archive.org. You could browse through this alphabetical book and it is for free. You could also search it on Ancestry.com. The other thing is that if he had patriotic service.What that means, Fish, is that he did something for the cause, essentially, supplied horses or guns or money or something. But you need to find the primary source that actually indicates it, so like a receipt or something that they were serving as town officer or something of that nature at the time of 1775 to 1783. So, there are all sorts of ones. Some people took oaths. I think there's one for New York.

Fisher: Yeah, there is and I had an ancestor in that situation. It’s called the Articles of Association. And it was signed around New York State between June and July of 1775, and sometimes it’s called the Revolutionary Pledge, and the purpose was to bring people to the point of associated effort. It had no direct reference to an appeal to arms or separation from the English government, but still, if your ancestor signed that in New York, then they are eligible for SAR and DAR as a result of patriotic service. So, every state seems to have a little something different and obviously at that time, there were only 13 colonies, so you might want to see where your ancestor was and if there was something unique like that for the state your people were from.

David: Well, one of the things that you could consider is of course if they were at a tea party. So, Boston had tea parties, but there were other ones throughout the colonies where they consider those as patriotic service as well.

Fisher: Sure. Yeah, absolutely. And those are kind of hard to figure though, because there really wasn't a role call taken of who those people were at those tea parties, right? I mean, I know there was a list that was published in the paper, like in the early 1800s, but those are people long after the fact, maybe wanting to say, "Yeah, I was part of the gang."

David: You know, that's very true. In fact, I was on a genealogy subcommittee for the SAR where we're looking into the qualifications. I mean, and to be perfectly honest, those at the Boston tea party didn't, like, "Hey, I did this!"

Fisher: [Laughs] No.

David: There’s no like a lot of first accounts. It’s mostly their children and grandchildren after the fact saying, "Oh yeah, my parents were there." It’s kind of like in 100 years and people say their great grandparents were at Woodstock.

Fisher: Yes. [Laughs] Exactly right, yes. I actually had a school teacher who was at Woodstockand came back to school that fall talking all about it.

David: [Laughs]

Fisher: We thought he was the coolest teacher in the world. All right, that was a great question, Missy. Thank you so for that and hope that helps a little bit and helps others figure out if maybe they have some ancestors eligible for the Daughters of the American Revolution or the Sons. And when we return in three minutes, we'll answer another one of your questions on Ask Us Anything on Extreme Genes.

Segment 5 Episode 326

Host: Scott Fisher with guest David Allen Lambert

Fisher: All right, back for our final segment of Extreme Genes. It is Ask us Anything. I am Fisher. That's David Allen Lambert from the New England Historic Genealogical Society and AmericanAncestors.org. Our next question, Dave, is from Rick in Little Rock, Arkansas. He wants to know about school records. He says his mother graduated in 1940 from a high school. He knows there are some records available online, but is there anything more that might give him a little insight into her educational performance? [Laughs] David? Good question.

David: Well, I’ll tell you, Rick that's a really fun thing to research. My own grandmother's report cards from 1914 were still with the guidance department of her high school when I wrote to them about 30 years ago now. They had down in the basement in old wooden cases all the report cards. So, if you ever wanted to know how your mother did in biology or in math, here's your chance.

Fisher: Oh wow!

David: So, they usually have these transcripts and some school departments dump them after a certain amount of years. My own high school unfortunately, did that a number of years back. It always goes to show, its best to act as soon as possible for records. The statutes of limitations are going to vary from school district to school district. Now the other thing is, your mom in 1940 is probably in a yearbook. So, there are a lot of year books that are on Archive.org. Besides, Ancestry.com has digitized a lot of those. I've seen a lot of friends in the genealogy community, their lovely high school photo. [Laughs]

Fisher: Yeah. [Laughs]

David: The other thing is that you could go onto eBay, Rick, and you could put in a search for 1940, the town your mother's high school was in, and the word "yearbook", set it as an email alert and you'll find out as someone goes to sell one. I constantly am buying the old 1930s and 1940s high school yearbooks from my town, because they're genealogical tools now.

Fisher: Sure, yeah. And actually, I found all of my dad's yearbooks. He was quite a bit older when he had me, so this was kind of fun, because they went from 1928, 1929, 1930 and 1931 and they had belonged to one of his classmates who went through all four years together with him. And I found my dad had signed all four books, one of them when he was 14 years old.

David: [Laughs]

Fisher: And there were pictures in there. I mean, some of them we had in our family photos, but there were about ten of them in there that I had never seen before. Pictures of him on the basketball team, on the baseball team. I didn't know, for instance that he had been part of student government from his earliest years. And he was also the leading salesman for magazine subscriptions and actually set the New Jersey State record and then a national record. It’s like, I had no idea he could sell! He was a musician. Who knew?

David: Well, you know, it just goes to show you the hidden treasures within the yearbook and of course all the notes that are in there, thinking of re-associating people that are descendant from the ones that wrote an inscription or put a little note in there. So, it’s really a fun time capsule.

Fisher: Yeah, it really is. It’s a great way to go. It’s a great pursuit for you, Rick. And good luck in that. And hopefully somewhere around where your people were, maybe they've held onto some of these records a little longer than elsewhere, because I think it’s rather arbitrary when schools get rid of some of their records. Some are required by the school district to hold onto them for a certain period of time. And some of those records may last a lot longer than that time period, you know. You never know.

David: That's right. So, send in your questions.

Fisher: [Laughs] Make sure you get aggressive and write to those people and see what they can find. You never know what's going to come up. And good luck to you there. Thanks so much for the question. And if you have a question for Ask Us Anything, all you have to do is email us at, get this, [email protected]. David, thanks so much. We'll talk to you again next week.

David: All right my friend, stay well.

Fisher: All right, thank you, sir. And that's our show for this week. Thanks so much for joining us. Thanks once again to the Legal Genealogist, Judy Russell for talking about the legalities of quarantine, some of the history of it. If you missed any of the show, of course, catch it on ExtremeGenes.com, iTunes, iHeart Radio, Spotify, TuneIn Radio, there's so many places. We'll talk to you again next week. And remember, as far as everyone knows, we're a nice, normal family!