Episode 337 - What’s There? Fisher Gets His “Big Reveal” On DNA From Family Envelopes / Melanie McComb On Researching Minister Ancestors

Aug 09, 2020

Host Scott Fisher opens the show with David Allen Lambert, Chief Genealogist of the New England Historic Genealogical Society and AmericanAncestors.org. The guys open with the latest news on the GEDMatch security breach. Then, Delaware is removing a public whipping post, largely used to punish African-Americans for petty crimes. Hear where it’s going. Next, it’s another son finding another car that once belonged to his father. Only this time it’s a unique car and it’s over in England. Catch the details. A woman who qualifies as a “Rosie the Riveter” from World War II is back serving her country again. Find out what this amazing woman is doing. Fisher next updates everyone on the latest with Ancestry and their raising of the limit for a match from 6 centiMorgans to 8.

Fisher then follows up his visit from last week with Karra Porter, co-founder of Keepsake DNA. Today she reveals to Fisher whether any of his four ancestral envelopes that he supplied had sufficient DNA from which kits might soon be created. Be there for his “big reveal!”

Melanie McComb, longtime friend of the show from NEHGS, then shares her knowledge of researching family who served in the clergy. You might be surprised at how much information can be found on these relatives and how much information on their family might be a part of it.

David Lambert then returns for a pair of questions on Ask Us Anything.

We cover a lot of ground this week on Extreme Genes, America’s Family History Show!

Transcript of Episode 337

Host: Scott Fisher with guest David Allen Lambert

Segment 1 Episode 337

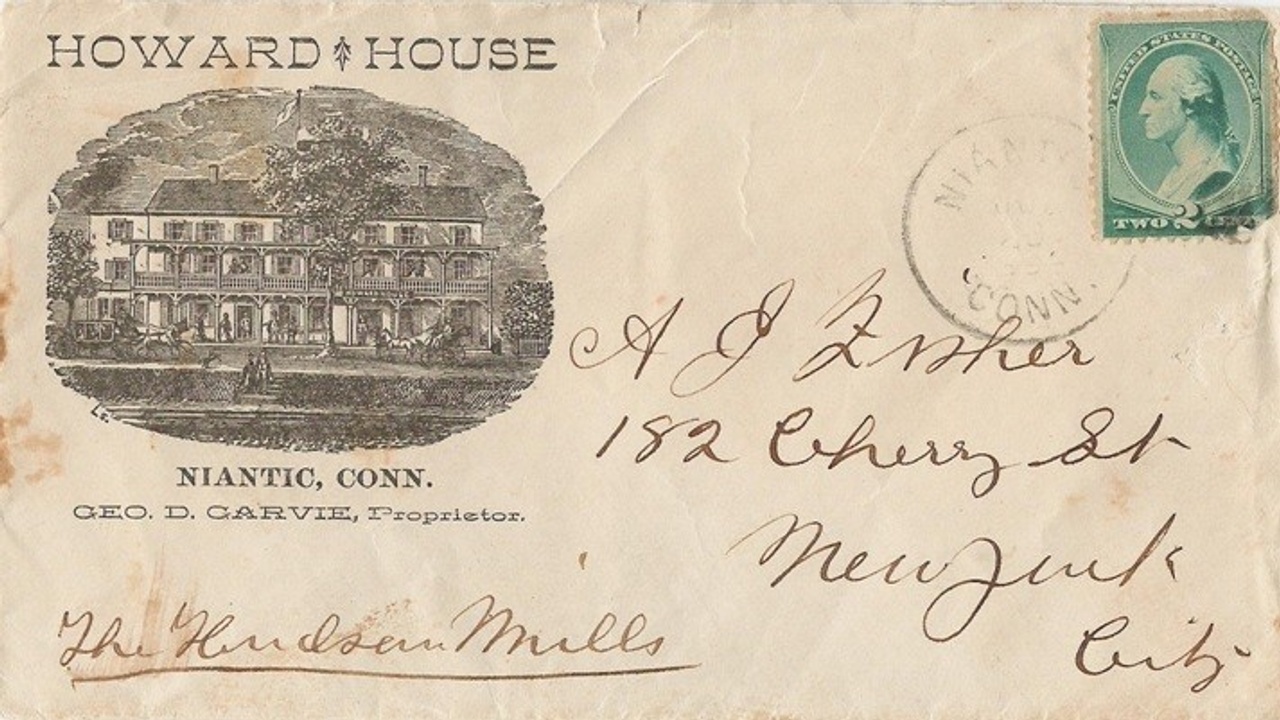

Fisher: Hello genies, and welcome to America’s Family History Show, Extreme Genes and ExtremeGenes.com. It is Fisher here, your radio roots sleuth, on the program where we shake your family tree and watch the nuts fall out. Well, today is the big reveal. Remember, last week we talked to Karra Porter with the new DNA lab. It’s called Keepsake DNA. And, as a little test she took four envelopes, licked by my relatives and ancestors, to see if we could get a DNA profile off of them, one of them dating back to 1912, the other three from the 1950s, so they’re 60 to 70 years old. And what can you do with them? Will there be enough DNA on these to create a profile that you could put on GEDmatch? We’re going to find out in about ten minutes, and I can tell you right now, I can hardly stand the anticipation. [Laughs] This is so exciting and they’re also going to be able, by the way, to test hats and earrings and dentures and hearing aids of your ancestors. You never know what you’re going to be able to do with DNA moving forward with this. So, we’ll see what happens with Karra in just a little bit. Hey, if you haven’t signed up for our “Weekly Genie Newsletter” yet, please do so. It’s absolutely free. You can sign up in our website ExtremeGenes.com or on our Facebook page. You can get a blog from me, a couple of podcasts of past and present and stories you’ll be interested in as a genealogist. Right now, it is time to head out to Stoughton, Massachusetts. David Allen Lambert, he is self-quarantining in his own home with all kinds of info today. How are you doing David?

David: I’m doing okay and I’m doing a lot better now that GEDmatch is back online.

Fisher: Yes! And this is good news obviously. They’ve gone through quite a problem here with the exposure of everybody’s information for about three hours a couple of Sundays back. But they are back in business and your choice now what to do with that. Of course, it is still a great tool for genealogists, but you just have to kind of measure your level of comfort with some of the things that have gone on there. But hopefully, they fixed whatever the problem was in the first place, and we’ll see where it goes, moving forward.

David: That is very true. In our Family Histoire News we go to Delaware where remnants of the past, trying to be forgotten, and probably should be, are the whipping posts. When you think of a whipping post, I think of colonial New England, some cedar posts in the center of the town. It was legal until 1972 to have public punishment of whipping in Delaware.

Fisher: Yeah, and so this is a whipping post in Georgetown, Delaware, and they’re actually removing it from public display. It’s got a little fence around it and they’re just going to store it away some place. A lot of people were just saying the sight of it in public was disturbing, and in many instances, it was used on African Americans for petty crimes like shoplifting or something like that. So, it’s got a very nasty history and it’s a great thing to see that just being put aside in some building.

David: You know, it’s really scary to think that something like that was law in our lifetime. Saying goodbye to that history is a good thing. You know, I don’t know about you, but get rid of a car and don’t expect to see it again, or hopefully my kids won’t see it after I’m gone.

Fisher: [Laughs] Right.

David: Like my 1978 four door lime green Caprice Classic, that’s probably a soda can somewhere in Taiwan right now.

Fisher: Right. [Laughs]

David: But some people are searching. And you told me when we were talking earlier, another person just found his dad’s car.

Fisher: Yes, this is over in England. Somebody on eBay was poking around there, and they found this 1978 Vauxhall VX90, and was painted like patrol cars from this guy’s hometown in Durham, in England. And he said it looked really familiar. Well, that’s because it looked just like the car that his dad Barry used to give high performance driving instruction for the Durham Constabulary. Yeah, and he was going through the images associated with it and there was a document signed by his dad and he realized, “Oh my gosh, this was Dad’s car!” So, he says, “You could have picked me off the floor.” He says, “I haven’t seen it in years and years and years obviously.” Well the owner lived 300 miles away. And when he bought the car, the car hadn’t run so this guy spent all his time in lockdown restoring it to make it roadworthy again. So, this guy, Greg Barnett, he didn’t waste any time. He paid $11,500 to bring it back to Durham thirteen years after his dad’s death. He even has pictures of himself as a child standing next to this car.

David: Oh boy. Well, you know, last year we talked about the passing of a lady who was recognized as Rosie the Riveter from the “We Can Do It!” campaign from World War II. Now, there are plenty of Rosie the Riveters still with us. Ladies that worked in factories to help the war effort in World War II, and they’re mostly in their nineties. Now, Mae Krier who is of Levittown, Pennsylvania is 94 and she’s still working. Do you know what she’s doing Fish? Making masks.

Fisher: Yeah, she made bombers in Seattle back when she was seventeen years old, 75 years ago during World War II. And here she is, a Rosie the Riveter, still fighting for her country, in this case she’s making masks to prevent the spread of COVID-19. What a great story.

David: I know. I hope that she makes some of the B-17s and B-29s on them. That would be cool.

Fisher: [Laughs] Hey David, before we take a break here, I just want to remind everybody that AncestryDNA announced just last week that they’re going to be raising the threshold for matchdom, if you will, from six Centimorgans up to eight Centimorgans. So, if you’re into your family history DNA you’re going to lose a whole bunch of matches. The idea is to reduce the number of false matches by like two-thirds by cutting it off at eight Centimorgans instead of six. However, if you have messaged any of these people, or you have saved them in a group of matches or made some notes relating to that person, those matches you already have will not go away. They haven’t put a specific date on it. It’s going to be sometime in early [now late] August that this happens. So, you do have some time to go back and make sure that you have marked anybody that you think might be a significant match to you that’s in the six or seven centiMorgan range. I know a lot of people right now are going through and creating an entire group just for all the six and seven centiMorgan matches. I started to do that David. The list is forever. [Laughs]

David: [Laughs]

Fisher: It’s just like no, I don’t think so. I will save the ones that also have an ancestor in common with me, and maybe a few others that seem suspicious, but that’s about it.

David: [Laughs] Right.

Fisher: David thanks so much. We’re going to have you back here in just a little bit of course, for Ask Us Anything. And coming up next, we’re going to talk to Karra Porter from Keepsake DNA. It’s my big reveal as she talks about the potential for DNA profiles being created from DNA left on envelopes of my ancestors and relatives, when we return in three minutes on Extreme Genes, America’s Family History Show.

Segment 2 Episode 337

Host: Scott Fisher with guest Karra Porter

Fisher: All right, we started this last week and today we get the results. It’s Fish here. It’s Extreme Genes, America’s Family History Show. I’ve got Karra Porter back, one of the founders of Keepsake DNA. It’s a brand new lab that’s testing old envelopes, and hats, and earrings, and dentures, and hearing aids. And last week of course Karra, I sent you four envelopes with ancestral significance there, and you’re telling me you’ve got some results?

Karra: We do. And this is the first time that we’ve talked about these.

Fisher: Yep.

Karra: So, I hope you’ve got your list in front of you because I’ll just go through in the order that I’ve got notes. Are you ready?

Fisher: Yes. Yeah, let’s go through it.

Karra: Okay. Item one was a small white envelope stamped Freeport, November 7, 1950.

Fisher: Um hmm.

Karra: You have that one?

Fisher: Yeah I know that one. That’s my grandfather’s half sister who he never knew. And so, she would have half of my great grandfather’s DNA.

Karra: Well, unfortunately I have disappointing news for you on that.

Fisher: Uh oh.

Karra: That was male DNA.

Fisher: So, somebody else licked the envelope.

Karra: Somebody else licked the envelope.

Fisher: Okay.

Karra: That’s unfortunate. That’s one of the risks. Now it may of course still be somebody that you care about, a relative, or…it’s interesting I can tell you. I mean, the male of course is the biggest thing for you, but from my notes, this was a single source male. There was no discernible DNA degradation.

Fisher: Oh wow.

Karra: Yeah, which is pretty good for a 70 year old envelope.

Fisher: 70 years, yeah. That’s incredible. Okay.

Karra: Yeah. The amount of autosomal was .330 nanograms, so 330 picograms, which is a little on the lower side. We like it closer to a nanogram.

Fisher: Um hmm.

Karra: But we would expect to get a useable profile from that.

Fisher: Okay.

Karra: Now, again, it will be a decision since it did not turn out to be female DNA. The postman may have licked it, or somebody else in the household.

Fisher: [Laughs]

Karra: I’m sorry about that.

Fisher: No, I am too. We will have to find another envelope from her potentially, because she’s the only person on the planet who might have left something with that DNA we’re looking for. But that’s great. I mean, it’s interesting to know this and how it works, and the process for people listening right now. That’s why we’re doing it. What have you got next?

Karra: Okay. By the way, for anyone out there that is a scientist or works in a DNA lab, these are just little summary notes. The report itself of course has a lot more detail.

Fisher: Sure.

Karra: But the second item that you sent us, a small envelope stamped Albany, December 1, 1954.

Fisher: Yeah. This would have been not long after I was born. This was my grandmother, my maternal grandmother in Albany, Oregon.

Karra: It’s male DNA.

Fisher: Male DNA? Who’s licking all these envelopes? [Laughs]

Karra: I’m telling you I know, I will say this, actually I probably should clarify that because of the .513 nanograms, so 513 picograms.

Fisher: Uh huh.

Karra: It showed .284 nanograms of male DNA, which means that there is probably a female component in it.

Fisher: Okay. So, how does that work?

Karra: So, that would be a mixture of male and female. The way that works, and I’m going to grossly oversimplify it and have any DNA person listening out there ripping their hair out at my language, but the way I understand it as a lay person, the way that the mixtures work, the equipment that we have, can separate out mixtures quite easily for identification purposes. So, for example, if we were trying to figure out whether the donor of that DNA sample murdered someone, we could separate that particular sample out pretty easily and say yeah, that’s the killer, or, that’s not the killer. With respect to coming up what we call the SNP profiles, you know, the profiles that will be uploaded to GEDMatch, it’s a little more complicated but it can be done if there’s enough differential between the genders. And actually, when we get to item four I can explain this in a little more detail.

Fisher: Okay. Let’s move on to item number three. I feel like a game show host here! What’s behind the door, you know? [Laughs]

Karra: Well, this does illustrate some of the risks etc.

Fisher: Sure.

Karra: Some of the adventure I guess of this. I don’t know.

Fisher: Right.

Karra: Item three was a white envelope with red and blue on the edges and it was stamped New York, July 16, 1951.

Fisher: Yeah, New York City.

Karra: Okay. So, do you know who that one was?

Fisher: Yeah. This was my father.

Karra: Oh, okay. Well, it produced a very large amount of DNA. It actually produced well over one nanogram!

Fisher: Oh that’s awesome! [Laughs]

Karra: These are my notes, single source male. It was fairly degraded. It was more degraded than any of the other samples.

Fisher: Um hmm.

Karra: Which the lab director indicated could mean that one time it was subjected to high heat.

Fisher: Okay.

Karra: Or moisture or something. But, it’s a good amount. The degradation probably will not affect the ability to get a good SNP profile from that.

Fisher: Wow.

Karra: Mostly because SNP sequences are small fragments, and it’s the longer fragments that we would be expected to be affected by this degradation. So, in a nutshell, there are no guarantees but we would expect to get a good GEDMatch type profile from that sample.

Fisher: Well, from which we could find new matches. And since he has obviously twice the DNA from his side of the family than I would have, then there’s a big potential for more matches, right, to come from further back.

Karra: Oh yeah. The most ideal thing is to have like one from your mother and one from your father. And for one thing, when you are just running your mother’s DNA it’s going to exclude most of the matches to your father and vice versa. But yeah, his DNA will produce more matches and more quality matches. And it’s pretty exciting. I mean, that’s the whole reason we went through all the trouble of trying to get my mother’s father’s DNA and then why we ran her. She only had one living brother. He died about 20 years ago, but we got like 10 nanograms with almost no degradation out of his letter from 1987.

Fisher: Wow.

Karra: Okay. You had another item which was over a hundred years old. It was a light brown envelope stamped Salt Lake City, November 11th, 1912.

Fisher: Yeah. This is my mother’s paternal grandfather, so, one of my maternal great grandfathers.

Karra: According to the report, the result on this appears to be mostly female with a small male component.

Fisher: Hmm. Okay. Because this was a letter he wrote to one of his daughters, telling her that his mother had passed away, my great, great grandmother, and what the funeral arrangements were, and even the envelope was written in his hand.

Karra: I’m looking at .482 nanograms. And of that, the Y portion was only .076 nanograms, so that is mostly female with a small male component.

Fisher: Um hmm.

Karra: I mean, that one, because there is a big differential, it’s not like a 50/50 it’s more like a 90/10 or whatever this math would be. And so that it probably would have a good shot at being sorted out.

Fisher: Really? Okay.

Karra: Separated out.

Fisher: Um hmm.

Karra: The major component from the minor component. So, if the male part, he just took it to the post office and she licked it or something, then those probably could be separated out because of the differential.

Fisher: Interesting.

Karra: That one was only slightly degraded even though it was over a hundred years old, so it was well stored.

Fisher: Isn’t that something. [Laughs] Amazing.

Karra: It’s weird. You don’t know what you’re going to get. I remember when we ran my mother’s brother’s envelope and I was just really, really hoping that his ex wife or his neighbor or whatever had not licked it. You just don’t know. That is the risk.

Fisher: Right, right, right. Well, what I’m excited about here is my dad’s. I mean I have really, I think that was my only shot that I had with him because I’ve got letters he wrote, he wasn’t a prolific letter writer, but that was a letter he wrote to my mother when they were dating. She was in Reno, he was in New York and they had met in Reno when they were both filing for divorces.[Laughs] So, you never know.

Karra: Oh my. I guess that was meant to be, wasn’t it?

Fisher: Yeah. That one I had no expectation that there could possibly be a female involved in that letter. It was very personal. He was living alone in the city at the time. There wasn’t any chance of that. But if we can get a profile out of that, that would be amazing.

Karra: Yeah. I mean the thing is, we were able to get good results on these, and frankly, on nearly every other envelope that we tested. We’re going to be posting a thing of all of the envelopes that we’ve tested. And we’ve gotten really amazingly good results off of them. What we don’t know of course is, did the neighbor lick it.

Fisher: [Laughs]

Karra: We had one in this latest batch it looks like somebody used a sponge because we literally got zero quant, which doesn’t happen. I mean, you make it a low quant or degraded or something to get zero. Somebody just used a sponge or something or that. We were disappointed in that. But the ones where there are DNA, we’re getting DNA from the vast majority of them even going back 100/150 years.

Fisher: Wow.

Karra: But the problem is you don’t know. I mean, did people just leave their envelopes in one location and then one person would take them all and lick them all? We don’t know.

Fisher: Interesting. Yeah, I’m really surprised to hear about the degradation on that one envelope from my father because that was always kept in the house. They weren’t stored in attics or anything. But, there also a very thin envelope very thin paper and maybe that contributed to it.

Karra: Well, it also depends on how much of a secretor. I mean, on some of these envelopes we had like 50 nanograms.

Fisher: Oh wow. [Laughs]

Karra: I mean, we had some people that it’s practically like spitting in a tube. Others I mean it’s just kind of like the DNA in our hands. I mean, I don’t know if you’ve ever met any of those studies, but some people are called shedders and some people aren’t. So, they’ve done a lot of studies, for example, you have the first person holding a water bottle or a coke can or something, for 30 seconds, hands it to the second person who holds it for 30 seconds, then hands it to the third person who holds it for 30 seconds. And then when they’ve tested that bottle or the coke can, they will find just widely varying results. Sometimes they will find no DNA of the second person or the third person, but they’ll find plenty for the first person or the second person. Do you see what I mean?

Fisher: Yeah.

Karra: They ran those tests over and over and it just depended on the degree to which each person is a DNA shedder, because we all shed it, but some more than others.

Fisher: Fascinating. Well, the company is Keepsake DNA. It’s a brand new lab and you got a little taste right now of exactly how it works and how it’s going to work. You can find out more at KeepsakeDNA.com. Karra Porter, thank you so much for running these. And we’re going to have to talk more in the future about okay, what’s the next step. And we’ll be talking about this I’m certain throughout the entire year ahead.

Karra: It sounds good. Appreciate it.

Fisher: Thanks so much! And coming up next, Melanie McComb talks about tracking down information about your clergyman ancestors, when we return in five minutes on Extreme Genes, America’s Family History Show.

Segment 3 Episode 337

Host: Scott Fisher with guest Melanie McComb

Fisher: All right, we’re back on America’s Family History Show, Extreme Genes and ExtremeGenes.com. Fisher here, your radio roots sleuth and we’re coming up on a lot of conferences happening right now. They’re all virtual. Nobody is doing anything live these days of course. My friend Melanie McComb from the New England Historic Genealogical Society and AmericanAncestors.org is on the list of speakers. And Melanie, you’ve got one coming right up, what is it?

Melanie: Hey, Fisher. Yes, that’s correct. We have the Celtic Connection Virtual Conference that’s been hosted by Irish Genealogical Society International and TIARA. (The Irish Ancestral Research Association) so all Irish over the span of a few months have been able to watch the videos. And one of the lectures I’m giving is how to research members of the clergy in your family tree.

Fisher: Oh, I like that.

Melanie: Yeah, because too often we’re looking into all the different family members, especially the ones who produced children and we’re not always looking into the priests, the nuns, the ministers, and all the other people that chose a different path in life. So maybe they didn’t move to have children or go on to do anything else but they had a higher calling.

Fisher: Right.

Melanie: And talk more about their journey and how they became part of the clergy.

Fisher: I am amazed how much information is out there on the people you speak of and most of them would be great aunts and uncles, most likely right, to people?

Melanie: Correct, right. I’ve had distant cousins for example that I’ve looked into, a few different ones, even a second great uncle, I found a priest in Ireland that I’m looking a little bit into as well.

Fisher: Wow. So where do you start? Obviously, records for priests in Ireland would be completely different from ministers in the United States or maybe Canada. I know you have all those backgrounds, as well as a Jewish background. So, I would imagine clergy on the Jewish side of things would be a little bit different as well. So, what area is it that you want to focus on here?

Melanie: Sure. So, one area that we want to think of to start looking into more about a member of the clergy, is starting to look at some of the places where they attended seminary school, that can be one area because that’s one place that I started to really dig into one of my distant cousins. His obituary gave a very long detailed resume history of his life and it even noted where he went to seminary school. And with the beauty of the internet, I was able to go online and find yearbooks, including photographs of him.

Fisher: Yeah, that is interesting too because yearbooks for people in that field often go way, way back.

Melanie: That’s right. And even if it’s not like modern photography, maybe you’ll see more of a portrait of someone that was often done. Remember, the clergy they often were written up in like church histories and other published documentation because they were considered notable citizens of their community.

Fisher: Right, right, right. I was just looking online there is a Catholic Record Society for instance, over in England and Wales, and in volume 30 there, they do a whole thing on registers of Valladolid which I assume was where they went to get their training.

Melanie: Okay.

Fisher: And in there was a Clement Fisher among the Fishers in this little village that I come from. And I remember seeing it, it’s all written in Latin so it’s very interesting, but it tells who his parents were, where he was from, certain aspects of his career as well. So, I thought that was really kind of interesting.

Melanie: That’s fabulous.

Fisher: Yeah, it’s really good. And a lot of them are written up in this way where they’ve been transcribed from original records and found in volumes on a particular topic depending on where you are.

Melanie: Yeah. And sometimes even with the clergy, the resume goes beyond the congregation. For example, one of my distant cousins actually was a war chaplain during World War I, and because he was serving in the Canadian Armed Forces his records were fully online. So I was actually able to go into his personnel file and it talked about all the different places where he was stationed, including noting what hospital he was serving into as minister and any kind of sacraments and any last rites of anybody that was in the hospital and it even noted when he was hospitalized for influenza, because this was at the height of the flu pandemic.

Fisher: Wow, so it became a military record that kind of revealed everything.

Melanie: Exactly. It started to talk a little bit more about what he did and then how he returned to go back to university to teach as well. So, it actually told us what he did after the war.

Fisher: Wow! And that’s fairly recent. You know, I hate to switch back on you from this, I was just kind of going through some of these notes I found, and here was a thing from the seminary priest, a Dictionary of the Secular Clergy of England and Wales 1558 to 1850.

Melanie: Wow.

Fisher: And it was written in 1977 and it mentions this same guy, and listen to what they said about him here. “He was the son of George Fisher. A butcher of Yarm, Yorkshire and his wife Elizabeth, and was born December 25th 1743.” So, right in that sentence we get his birth date, his parents, his father’s occupation and then it says, “He entered Douai.” Which I assume would be for his training “In 1766 and left for Spain 20th of May, 1768. He entered Valladolid 27th June, 1768, was ordained 23 December, 1775 and left for the mission April 22nd, 1779. He arrived in the London District May 22nd, 1779, joined big M, 1780 and then disappears.” But I mean what a lot of stuff and that’s just four type written lines.

Melanie: That’s great how much info they put in there.

Fisher: Isn’t it amazing? And this is entirely to your point.

Melanie: Yeah. So, it’s always good to see what else you can find about these members and one thing that is important to notice when you’re trying to look for some members of the clergy, is really understanding the religion of your family because that’s going to help you guide what resources to go to next.

Fisher: Right.

Melanie: So, for example, a lot of my father’s side is Roman Catholic, so I could use different directories like official Catholic Directory on sites like Archive.org. And they actually have a full list of all members of the clergy across the world. So, not even just in North America. So you can really dig in on someone and see if you can find out where they were, where they were stationed, even when they retired because they noted that information in those published reports.

Fisher: And you know the thing is too when you find the record of these people, they’ll talk about their family too and where they came from and other relatives and occupations beforehand. There can be a lot of information just on the family which is just another reason why people need to research the siblings of your ancestors and others in the family.

Melanie: Yes.

Fisher: I’ve tracked down two, third great grandchildren of some of my ancestors and found that there was a biography written of them and it talked about the ancestor that I come through and where they came from, say in Ireland. And I’m thinking, where else would this come from? It was passed down that family line and published but otherwise there was no record. So, it was a great clue.

Melanie: That’s right. Yeah, you definitely need to make sure that you’re branching out everyone in your family tree because you never know when that next clue is going to come in and someone in the clergy would be a really good source of information just for breaching our the family.

Fisher: Yeah. I wouldn’t think there would be as many biographies about say, farmers, because as you mentioned at the beginning the clergy are such members of the community in high standing. You might find a lot more information right here than anywhere else.

Melanie: Definitely. Yeah, I know that when I was looking for information about my great grandfather that left Ireland, the reason why his obituary stuck out in an Irish newspaper was because his brother was a priest. The very Reverend Pierre Horkoran was one of the priests of the area. So, they had a nice big mentioned of his brother in there and that’s how I was able to know that we had the right family.

Fisher: Prominence really has a lot to do with what you can find sometimes. What about Jewish clergymen? Have you found a lot of success with that on one of your Jewish lines?

Melanie: So, nobody directly in my family, but I have looked in a couple of different records. So, I actually did a little research in the Boston City Archives several months back before the pandemic hit and one of the things I looked into was they had several different rabbi licenses.

Fisher: Oh.

Melanie: So these were actually issued to the vital records office of the registry department and they were coming from a specific synagogue. And the parish that was signed in their letterhead noting that here was the new rabbi installed for their one year term, you know, so they had to renew their contract.

Fisher: Um hmm.

Melanie: And it would note when they were permitted to marry others within the synagogue. So that was a lot of great information and some of those licenses even had vital records noted.

Fisher: Well, great stuff as always Melanie. Great talking to you, thanks so much.

Melanie: You too.

Fisher: And I think that’s going to inspire somebody I know to find something great about their ancestors as a result of this conversation. We’ll talk to you again soon.

Melanie: All right. Thank you.

Fisher: And coming up next, David Allen Lambert returns for another round of Ask Us Anything on Extreme Genes, America’s Family History Show.

Segment 4 Episode 337

Host: Scott Fisher with guest David Allen Lambert

Fisher: All right, back at it on Extreme Genes, America's Family History Show and ExtremeGenes.com. Fisher here with David Allen Lambert, the Chief Genealogist of the New England Historic Genealogical Society and AmericanAncestors.org. We're doing Ask Us Anything. And David, our question is from Pam in Midvale, Utah and she says, "I found a record of an ancestor where he died on the 10th day of the 8th month of 1682, but other sources, including his gravestone says he died in October of 1682. How can October be the 8th month?" [Laughs]

David: [Laughs]

Fisher: All right, David, begin.

David: Okay. Well, back in the 1500s, we swapped from using a calendar from the time of Julius Caesar known as the Julian calendar and most of Europe was changing over to what was under Pope Gregory, the Gregorian calendar. Yeah, well England and its colonies didn't see fit to do that, so between January 1st and the end of February, you may see double dating, like it may say, January 10th, 1631/2. Now, old style would be that date and new style would reflect that it is really 1632, because, you know, January is now in the present calendar as the beginning of the months, not the end of the year.

Fisher: Right.

David: Because before, the year ended at the end of February and began on March 1st. So, if March is your first month, October is your 8th month. And that makes sense as to why she's finding the 8th month as October comparing it with like, say, a gravestone, etc.

Fisher: So when did it reach the point where the calendar year ended on March 24th and began with the New Year on March 25th?

David: Oh, 1752 is when the big change happened, and then we lost days. I think there's some days, I believe in the fall that are not on the calendar at all.

Fisher: It’s like 11 days I think we lost that year, right?

David: Um hmm.

Fisher: Because it changed the date of George Washington's birthday. Nobody really knew when to celebrate it, was it February 11th or February 22nd?

David: What birthday do you really have for your ancestor back in the 16, 1700s before 1752? If it is between January and February, you guess. [Laughs]

Fisher: [Laughs] And you know, it’s interesting too when they reversed the numbers, for instance, in old Europe, you would have the 8th day of the 10th month, but then eventually became the 10th month and the 8th day. So you will see all kind of concocted dates for people's births, deaths and marriages based on that information and you don't know if the month came first and then they said, "Oh, the 8th month, well then its October, or wait a minute, no, that would be August. But was it the 8th day of?" whatever the other month, you know, I mean it could get very complicated.

David: It really is. And I think especially with newbie genealogists, why would there be two years to begin with, let alone like a town like Lowell, Massachusetts has their vital records that says the 4th day of the 9th month in, say, 1667. And it’s like, most people say, "Oh, it’s going to be September." Well, it’s not September. And I see people where that error is placed that there's a two month spread on the dates. So, let's say if you have two months off on a date based on that and then you have the 11 day difference. So technically, could you get like four birthdays out of a person that way? [Laughs]

Fisher: [Laughs] Well, it is complex and this is the reason why before the Hardwicke Act of 1752, you really have to do your homework and make sure you know exactly what you're dealing with here, you know, whether the month that is printed out as August was actually shown as the 8th month, which really meant October or was it the 8th day of some other month, you know, I mean, it’s really complicated. And that's why, you see, as you mentioned, David, the double years listed. And if you have to put in one, generally you want to put in the second date, because January and February and the early part of March was generally in the second date as we reckon it by today's calendar.

David: That's very true.

Fisher: All right, great question, Pam, thanks so much. We've got another one coming up for you as we continue with Ask Us Anything on Extreme Genes, America's Family History Show in three minutes.

Segment 5 Episode 337

Host: Scott Fisher with guest David Allen Lambert

Fisher: All right, more of Ask Us Anything on Extreme Genes, America's Family History Show and ExtremeGenes.com. It is Fisher here, your Radio Roots Sleuth. David Allen Lambert is there in Stoughton, Massachusetts, the Chief Genealogist of the New England Historic Genealogical Society and AmericanAncestors.org. And David, we hear from Jack in Tacoma, Washington. He says that his wife has French Canadian ancestry and he wants to know what is this thing about dit names, D I T names? [Laughs] That's a tricky little thing.

David: I wonder if it’s the same thing.

Fisher: Yeah.

David: Yeah, because I didn't have any French Canadian and my wife has French Canadian as part of her ancestry. So when I started looking at records and I see Boudreau, Alias Legere, dit Legere, I'm like, "What?! What is that? Why does he have two names? What did he do? Why does he have an alias?" I mean, the basic rule of thumb in a nutshell is that it’s a surname that has really an alternate name based on a variety of things.

Fisher: Yeah.

David: I've kind of chatted about this before.

Fisher: Why did they do it though, David, do you know?

David: My personal feeling is that probably because of the proximity of having so many people with the same surname. It’s sort of like in a village where you had John Smith Jr. when it was the younger John Smith and there wasn't a father and son combination.

Fisher: Yeah.

David: So maybe in an origin like that perhaps.

Fisher: That makes sense. Well, dit names, just a list of things that they used in them, physical characteristic, you know, long arm John. [Laughs] A name used in the army, land they owned, a location of origin, a nickname. They did this by the way in New Netherland with Dutch that had something similar with that and I've seen that with my ancestors. Do you know what? Sometimes they take the first and last name and combine it to form one new name. This basically created more than one surname for a lot of people and makes things very tricky. A dit name by the way, the word dit in French means to say or to speak. So, this is their said name basically or like you say, an alias.

David: And I can recall a book that we have at NEHGS back in Boston where you can look at it and you can see when a dit name was commonly found in the records. So, you may have a variety of different people with the same surname with a couple of different dit names in some cases too, because they changed it at a certain time in history, like you may have it in the early 1700s, but by the mid 1700s, they were using a completely other dit name.

Fisher: Wow! I mean, that is so! [Laughs] I'm glad I don't have a lot of that. And in fact, with Dutch names in New York that I have, it does get tricky with that, so I kind of relate to what you're going through with the French Canadian thing. There are all kinds of books by the way. There is a website called Family Names and Nicknames in Colonial Quebec that could be of use to you as you research different family names and try to sort out what the original names were and maybe where they came from, and sometimes where they came from is revealed among the dit names. So there's a lot of really stuff here that you can find online. So, great question Jack. Thank you so much for that. And of course we do Ask Us Anything every week, so if you have a question, it’s simple to do is email us at [email protected]. David, thank you so much and it was great having you on, and we'll do it again next week. You stay safe.

David: You as well, my friend. Take care.

Fisher: Well, this has been a memorable show. And thanks once again to Karra Porter for coming on from Keepsake DNA, sharing with me the results of their analysis of the four envelopes I sent over there, presumably licked by my ancestors and relatives from as far back as 1912 on one of them, and to know that it’s possible. Its sounds like for every one of them to potentially be made into a DNA kit and find matches to people who lived long ago, I mean, what an amazing thing that is! Find out more, listen to the podcast if you missed any of it on iTunes, iHeart Radio, ExtremeGenes.com or TuneIn Radio and Spotify. And thanks also to Melanie McComb for sharing with us information about finding information about your preacher brethren, because being stand out members in the community, their information can reveal a lot about your family, so find out more about that as well. Talk to you again next week. Thanks for joining me. And remember, as far as everyone knows, we're a nice, normal family!